Why Taking Control of Venezuela's Oil Industry Is Not as Simple as It Sounds

Technical Realities and Strategic Complexities Behind the World's Largest Oil Reserves

Executive Summary

Following the removal of Nicolás Maduro from power, U.S. policymakers would inevitably confront the question of Venezuela's oil sector. Venezuela possesses the largest proven oil reserves in the world, yet only a fraction of its potential production capacity is currently realized due to decades of underinvestment, sanctions, and institutional decay.

The assumption that the United States could simply "take over" Venezuela's oil industry obscures the technical and economic realities of Venezuelan crude production. The issue is not merely control, but oil quality, infrastructure constraints, and capital intensity, which make any intervention far more complex than it is often portrayed.

Key Findings:

- Quality Constraints: Venezuela's reserves consist predominantly of extra-heavy crude requiring specialized refining infrastructure

- Infrastructure Decay: Decades of underinvestment have left production facilities, refineries, and export terminals severely outdated

- Capital Intensity: Full modernization could exceed $200 billion over multiple decades

- Strategic Trade-offs: Each intervention pathway presents distinct advantages and limitations for U.S. interests

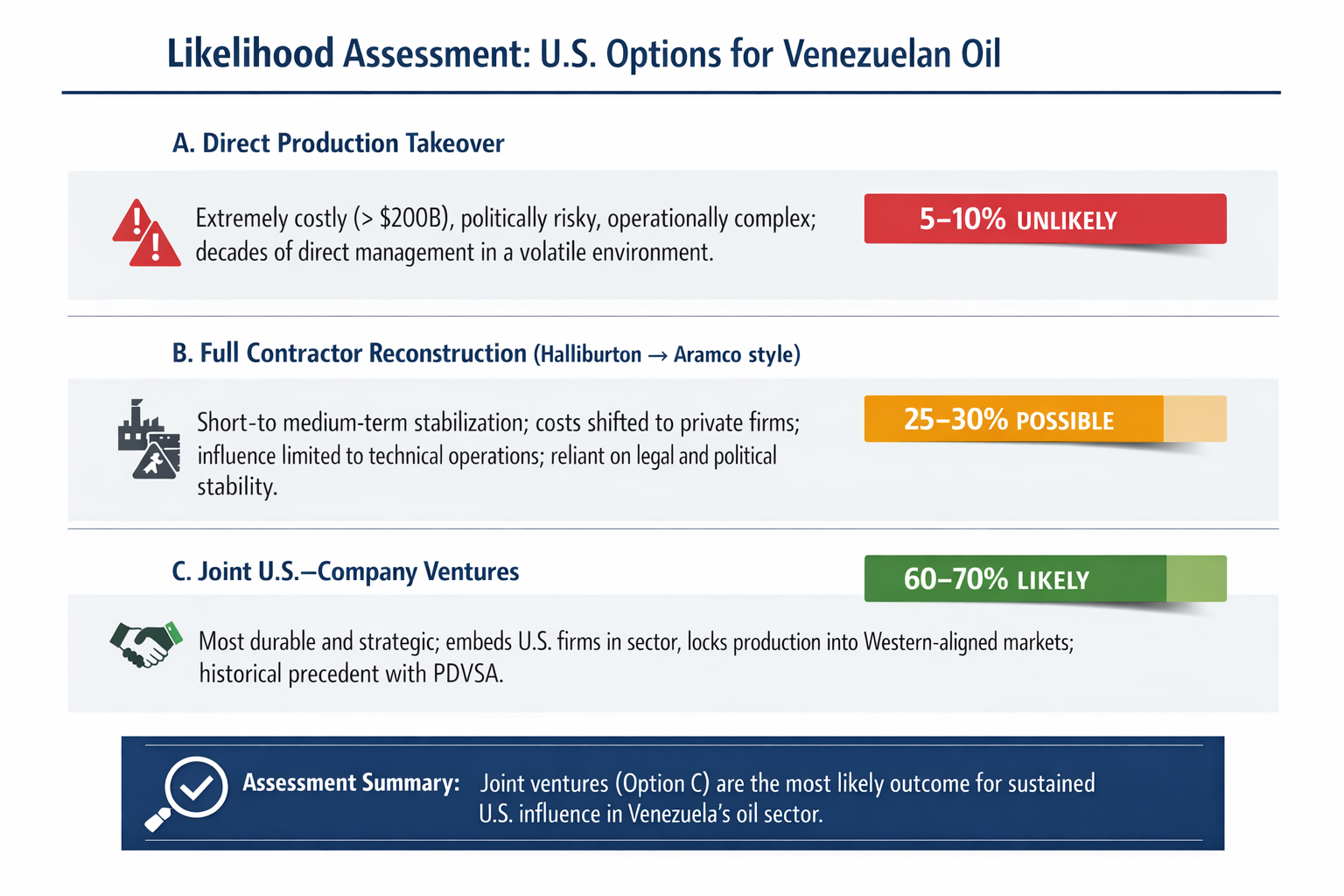

Three main pathways exist for restructuring Venezuela's oil industry, each with different implications for U.S. strategic influence, financial exposure, and long-term control. The optimal approach must balance immediate production restoration with durable strategic alignment.

Introduction

Following the removal of Nicolás Maduro from power, U.S. policymakers would inevitably confront the question of Venezuela's oil sector. Venezuela possesses the largest proven oil reserves in the world, yet only a fraction of its potential production capacity is currently realized due to decades of underinvestment, sanctions, and institutional decay.

The assumption that the United States could simply "take over" Venezuela's oil industry, however, obscures the technical and economic realities of Venezuelan crude production. The issue is not merely control, but oil quality, infrastructure constraints, and capital intensity, which make any intervention far more complex than it is often portrayed.

Crude oil is commonly grouped into broad categories—light, medium, and heavy—based on density and sulphur content. Light crude is the most commercially desirable, as it is cheaper to extract, easier to refine, and yields higher proportions of gasoline, diesel, and jet fuel. Heavy crude, by contrast, is more viscous, sulphur-rich, and requires specialized refining infrastructure such as cokers and hydrocrackers, significantly increasing capital and operating costs.

Venezuela's reserves consist predominantly of extra-heavy crude, particularly in the Orinoco Belt. Exploiting these reserves at scale requires extensive upgrading capacity, reliable diluent supplies, modern refineries, and sustained investment conditions that currently do not exist. As a result, Venezuela's oil sector cannot be rapidly or cheaply revitalized, regardless of political outcomes.

Table of Content

- Introduction – Technical and Economic Realities

- A: Direct Production Takeover – High Cost, High Risk

- B: Full Contractor Reconstruction – Strategic Limitations

- C: Joint U.S.–Company Ventures – Optimal Balance

- References – Source Material

Assuming broader U.S. strategic objectives are achieved, three main pathways exist for restructuring Venezuela's oil industry:

- Direct Production Takeover

- Full Contractor Reconstruction (Halliburton → Aramco style)

- Joint U.S.–Company Ventures

A: Direct Production Takeover

Direct Production Takeover

The Venezuelan oil industry is severely outdated, primarily due to decades of underinvestment compounded by U.S. and international sanctions that have bottlenecked necessary upgrades across the energy sector and its supporting infrastructure. Production facilities, refineries, pipelines, and export terminals suffer from technological obsolescence, poor maintenance, and workforce degradation.

A scenario in which the United States would directly assume control over Venezuela's oil production and infrastructure would be extremely costly and potentially counter-productive. Direct administration would require massive upfront capital investment, long-term security commitments, and responsibility for day-to-day operations in a politically volatile environment. Estimates suggest that fully modernizing Venezuela's oil sector—particularly its heavy crude infrastructure—could exceed $200 billion over multiple decades, especially if reconstruction is delayed into the 2030s.

Beyond cost, direct takeover would expose the United States to significant operational and political risks. Managing production, labour relations, environmental liabilities, and export logistics would place Washington in direct responsibility for sectoral performance, while also inviting domestic backlash within Venezuela and regional opposition abroad. As a result, a direct production takeover offers high financial exposure with limited strategic efficiency, making it the least attractive option among the three scenarios.

B: Full Contractor Reconstruction

Full Contractor Reconstruction (Halliburton → Aramco style)

Under a full contractor reconstruction model, Venezuela would retain formal ownership of its oil sector while foreign—primarily U.S.—energy contractors would be responsible for rebuilding, modernizing, and in practice operating much of the industry. This would include restoring production facilities, refineries, pipelines, ports, and export logistics, as well as managing technical operations and workforce training under long-term service contracts.

This model allows the United States to avoid direct administrative responsibility for Venezuela's oil sector while still ensuring that reconstruction is carried out by U.S.-aligned firms. It externalizes financial and operational risk to private companies and avoids the political cost of an explicit takeover. The contractor approach has precedent in post-conflict environments where rapid restoration of strategic assets is prioritized over institutional reform.

However, from a strategic perspective, this model has limitations. Contractors are paid for services, not ownership, which means long-term leverage over production levels, export destinations, and pricing remains limited. Influence is indirect and conditional on continued political alignment in Caracas. Moreover, large-scale contractor reconstruction would still require a relatively stable security and legal environment, which is unlikely in the immediate post-Maduro period. Without enforceable contracts and predictable governance, contractors would either demand inflated compensation or limit exposure.

In short, Scenario B is technically feasible but strategically shallow. It enables short- to medium-term stabilization of production but does not fully lock Venezuela's oil sector into a U.S.-aligned energy architecture. As a result, it is more useful as a transitional arrangement than as a durable strategic outcome.

C: Joint U.S.–Company Ventures

Joint U.S.–Company Ventures

Joint ventures between a restructured Venezuelan national oil company and U.S. energy firms represent a deeper and more durable form of control without formal ownership transfer. Under this model, foreign companies would hold equity stakes, share profits, and exercise partial operational control, particularly in capital-intensive areas such as heavy crude extraction, upgrading, and export infrastructure.

This approach directly aligns with U.S. strategic objectives. By embedding American firms into Venezuela's oil production structure, Washington ensures that output flows, technological dependence, and market integration are oriented toward U.S. and allied interests. It also crowds out rival influence by making Russian, Chinese, or Iranian re-entry structurally difficult without renegotiating core contracts.

Economically, joint ventures are more sustainable than contractor-only models. Capital investment is tied to long-term returns, giving firms incentives to modernize infrastructure rather than pursue short-term extraction. Risk is shared rather than front-loaded, and costs are amortized over decades of production. This makes large-scale reinvestment—particularly in the Orinoco Belt—more likely than under pure service contracts.

Politically, joint ventures provide plausible deniability. Venezuela retains nominal sovereignty, while real influence is exercised through corporate governance, technology control, and access to export markets. This reduces backlash compared to direct takeover while achieving more substantive control than contractor reconstruction.

The main constraint is institutional: joint ventures require a legal framework capable of enforcing contracts across political cycles. But from a U.S. perspective, this risk is outweighed by the strategic payoff. Even partial success would bind Venezuela's oil sector to Western capital and markets in a way that is difficult to reverse.

References

Venezuela Oil Sector Overview

Energy Information Administration. (2024). Country analysis brief: Venezuela. U.S. Department of Energy.

https://www.eia.gov/international/content/analysis/countries_long/Venezuela/pdf/venezuela_2024.pdf

Financial Times. (2026, January). Venezuela: Oil, oil everywhere — but not a drop to pump.

https://www.ft.com/content/060c5ede-bda4-49a5-9dfb-4fc939372ae0

Wikipedia. (2026, January). Carabobo Field.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carabobo_Field

Investment Costs & Reconstruction Challenges

MarketWatch. (2026, January 5). Paying over $100 billion to rebuild Venezuela's oil industry won't be the biggest obstacle facing U.S. oil companies.

https://www.marketwatch.com/story/paying-over-100-billion-to-rebuild-venezuelas-oil-industry-wont-be-the-biggest-obstacle-facing-u-s-oil-companies-bc5dcf5f

Chatham House. (2026, January). President Trump's ambition to rebuild Venezuela's oil sector will be challenging.

https://www.chathamhouse.org/2026/01/president-trumps-ambition-rebuild-venezuelas-oil-sector-will-be-challenging-especially-if

Atalayar. (2026, January). What will happen in the international oil market following the United States' intervention in Venezuela?

https://www.atalayar.com/en/articulo/economy-and-business/what-will-happen-in-the-international-oil-market-following-the-united-states-intervention-in-venezuela/20260107093742221998.amp.html

SIS International. (2026). Venezuela oil & mining industry potential: Strategic forecast 2026–2036.

https://www.sisinternational.com/th/venezuela-oil-mining-industry-potential-strategic-forecast-2026-2036/

Discovery Alert. (2026). Venezuela's oil revival economics.

https://discoveryalert.com.au/venezuelan-energy-development-strategic-context-2026/

Crude Quality & Refining Economics

Barron's. (2026, January). Venezuela's oil reserves: Economic impracticalities and reserve quality.

https://www.barrons.com/articles/chevron-stock-price-venezuela-oil-trouble-60d3e024

Discovery Alert. (2026). Venezuela oil access economics.

https://discoveryalert.com.au/economic-fundamentals-venezuelas-energy-revival-2026/

Foreign Involvement & Joint Venture Precedent

Reuters. (2024, June). Venezuela mulls extending Chevron joint venture through 2047.

https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/trump-administration-says-there-are-ways-us-can-lift-venezuelan-oil-output-2026-01-06/

Financial Times. (2026, January). Chevron as the sole major U.S. operator under sanctions.

https://www.ft.com/content/060c5ede-bda4-49a5-9dfb-4fc939372ae0

PolicyArchive. (n.d.). PDVSA partnerships and historical joint ventures.

https://www.policyarchive.org/download/2997

Sanctions, Political & Strategic Context

Associated Press. (2026, January). Oil stocks sharply higher after U.S. action in Venezuela.

https://apnews.com/article/0068fa49b414fafe8ccd4de0818a3dd5

The Guardian. (2026, January). Oil prices fall after Trump says Venezuela will send up to 50m barrels to US.

https://www.theguardian.com/business/2026/jan/07/oil-prices-fall-after-trump-says-venezuela-will-send-up-to-50m-barrels-to-us

Investopedia. (2026, January). Trump claims U.S. will "fix" Venezuela's oil industry, but experts warn of major challenges.

https://www.investopedia.com/trump-claims-us-will-fix-venezuela-s-oil-industry-but-experts-warn-of-major-challenges-11879406